Inside the old model museum. Elliot Carter photo

Before the National Portrait Gallery requisitioned the space in 1962, this beautiful room was the Old Patent Office model hall. Inventors used to have to submit working models along with their patent applications. As technology progressed during the Industrial Revolution this “Temple of Invention” was stuffed to the gills with intricate miniature machines.

Touring the Patent Office's models. Washington Post image

In its heyday, the Patent Office was one of the busiest office buildings in Washington. Every day, hundreds of inventors and attorneys from across the country came to search the patent records. The model hall predated the Smithsonian Institution by a decade and was a must-visit attraction for tourists.

The building was commissioned after Congress passed the landmark Patent Act of 1836 to collect “a general repository of all the inventions and improvements in machinery and manufactures, of which our country can claim the honor.” In it’s first year the Patent Office received 765 patent applications, but within 50 years the number of annual applications had grown to 41,048. The rate continued to increase year after year after that.

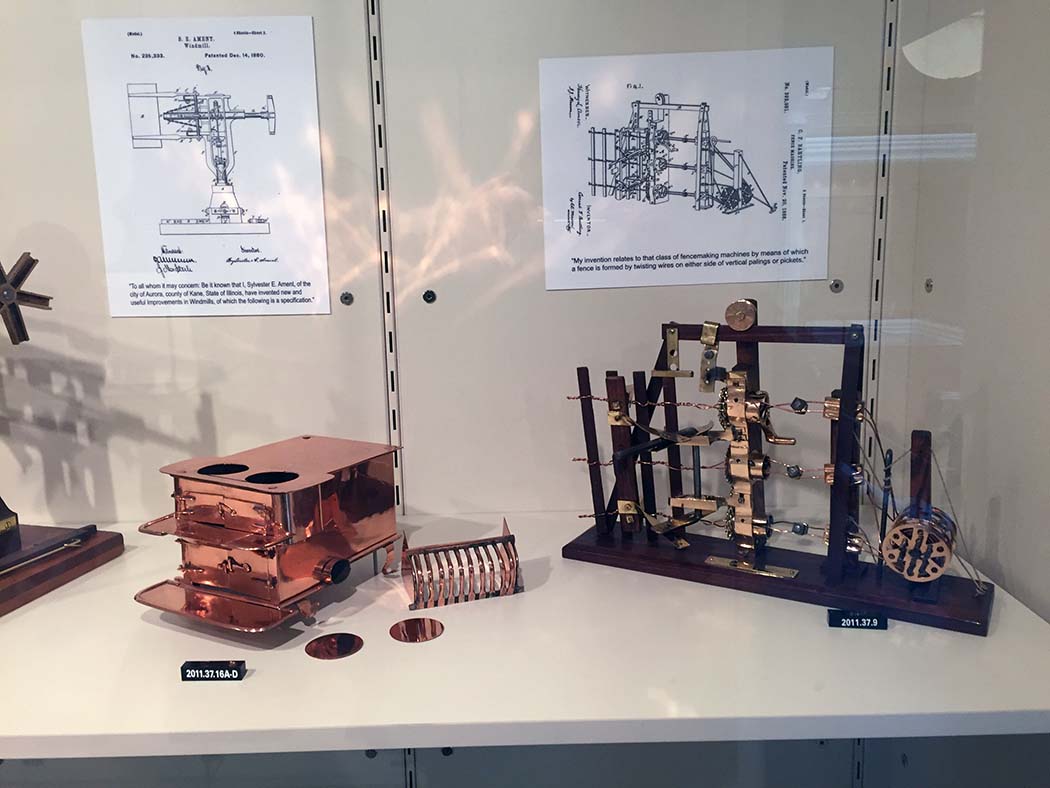

From 1836 to 1880 miniature models were a required addendum for all patent applications (The Washington Post explained this as a way to “get rid of the perpetual motion cranks”). The Patent Office collection brought in hundreds of thousands of these miniature wonders, creating a one of a kind industrial museum. Visitors could examine Eli Whitney’s mechanical cotton gin, Samuel Morse’s telegraph, George Westinghouse’s air brake, Joseph Glidden’s barbed wire, as well as 1,093 Thomas Edison inventions.

The patent trade supported a cottage industry of model shops in Washington. Several of the shops are visible in the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of the neighborhood around the Patent Office.

During the Civil War the Patent Office and its model hall were enlisted in the war effort for use as barracks and hospital space. Soldiers slept in three level bunks among the rows of glass cases.

Walt Whitman frequented the Patent Office during his service as a nurse. He described the “immense apartments” as “fill’d with high and ponderous glass cases, crowded with models in miniature of every kind of utensil, machine or invention, it ever enter’d into the mind of man to conceive.”

The decade after the Civil War was the high water mark for the Patent Office’s model collection. In 1877 a fire destroyed the third floor of the building and 87,000 models were lost. Finding space for all the models had always been a problem – The Washington Star wrote that “the government resorted to such storage places as the commerce building, the crypt at the Capital, and a rented garage at Seventh and F Street NW.” After the 1877 fire the government gave up and rescinded the model requirement from the patent application process.

Patent Commissioner examines models in 1925. Library of Congress image

In 1926 the Patent Office moved to get rid of the collection entirely. According to the Washington Star, “The Smithsonian looked them over and took about 15,000. The rest were sold at auction over six years beginning in 1926.” Many of the models were bought up by Sir Henry Wellcome, but his dream of a patent model museum was tabled by the 1929 stock market crash.

The Patent Commissioner with old models. Library of Congress image

In addition to the Smithsonian and Wellcome hordes, several private museums have amassed large collections of patent models. The Rothschild Peterson Patent Model Museum in New York has 4,000; The Hagley Museum in Wilmington has 100, the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn has 90.

The Old Patent Office Building itself was almost torn down in 1953. Congressman Charles Oakman thought that the property was the ideal location for a new parking lot that could “solve Washington’s downtown parking problem.” Thankfully it was saved from the wrecking ball by an early historical preservation campaign, and repurposed as the National Portrait Gallery. Today the old model hall houses sculptures and paintings.

Sculpture on display in the old model cases. Elliot Carter photo

Interested in other unique collections in Washington? Check out the Geography and Maps Division at the Library of Congress, and the US Navy's model ship program.