The 17th Street Dam. Elliot Carter Photo

These stone walls by the Washington Monument aren’t a part of any memorial or historic structure. They’re a temporary dam that can span 17th street and hold back a 100-year flood. The 17th street dam is the newest part of the 80-year-old Potomac Park levee.

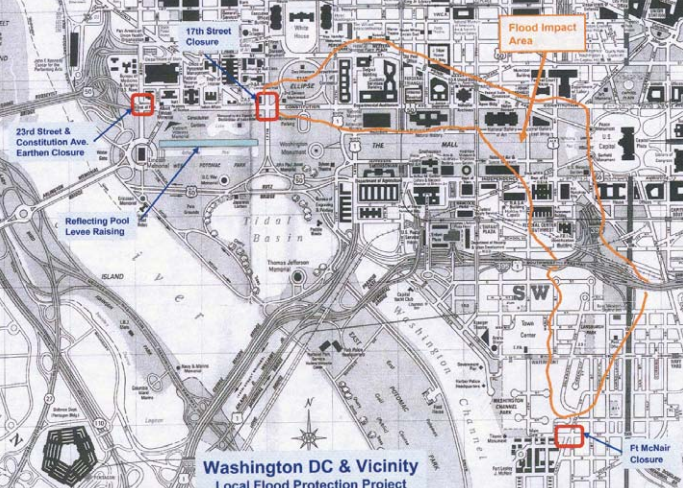

Washington's Federal Triangle neighborhood is uniquely vulnerable to flooding. First – the area is built on low lying land; if the river crests East Potomac Park it would quickly rush downhill and inundate the cross streets off Constitution Avenue. The second threat comes from rain runoff - Federal Triangle is the lowest point in a drainage basin stretching from the ballpark to Fort Totten.

Low lying land around Federal Triangle. Army Corps of Engineers image

The stakes are even higher because of what’s in those Federal Triangle buildings. Flood damage to the National Archives, EPA, IRS and Department of Justice could be devastating.

The original Potomac Park Levee was a temporary structure built by the Civilian Conservation Corps during a flood in 1936 to keep rising waters from reaching downtown. That weather event spurred Congress to authorize the construction of a larger earthen barrier and make the levee permanent. The Army Corps of Engineers completed the project in 1939. Most people walking along the sloping footpaths around the tidal basin don't realize that they're standing on manmade berms that were carefully laid out to prevent a watery disaster.

17th Street was the only gap in the levee - a deliberate but foolish engineering decision. Building in a gap offered two advantages. First it provided a pleasant even grade for automobile drivers traveling North-South. In the event of flood conditions, the plan called for a hastily built sandbag wall to plug the gap.

View from the Washington Monument in 1936. Library of Congress photo

The 17th Street gap offered a second benefit of centralizing the risk of a flood, so during a storm engineers could focus their efforts on a single preplanned fail-safe, rather than fighting the waters at a thousand different locations along the levee.

Unfortunately, in the case of the flood of 1937, 1942, 1972, and 2006 that wasn’t good enough.

Washington finally moved to address the issue in 2011 and began construction of the present day stone and cement structure. The gap in the center can be filled in with posts and panels that are capable of holding back waters up to 19 feet above sea level. They’re stored ready to go on trucks in Bladensburg and can be assembled in a few hours. The crews practice once a year to keep up their readiness and check the equipment.

Timelapse of the 17th Street dam. Army Corps of Engineers video

This is part four in a series of articles about Washington’s water infrastructure. Check out the previous articles on the Washington Aqueduct, the Lydecker Tunnel Fiasco, and the McMillan Sand Filtration Site.