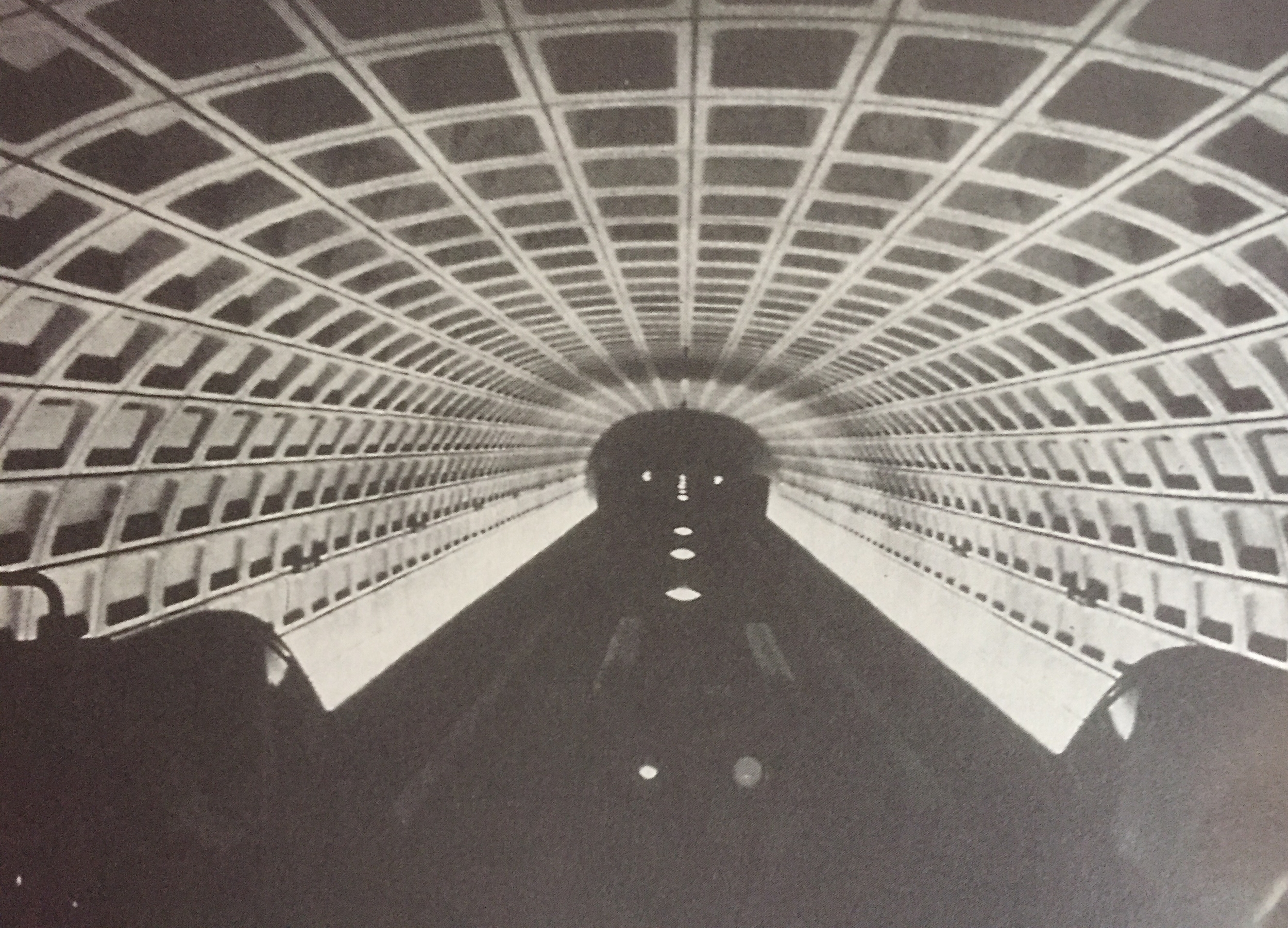

Tile installation at Ballston Station, 1978. WMATA photo

By Elliot Carter

Washington's Metro system opened for service to great fanfare in 1976. The initial line included just five stations stretching from Farragut North to Rhode Island Avenue, and it had taken seven years to build.

WMATA subcontracted the work to three consulting firms. De Leuw, Cather & Company worked out the engineering, Bechtel Corporation handled construction, and Harry Weese & Associates got to design the architecture . (Harry Weese was a talented architect who would go on to have an interesting career in Chicago.)

Harry Weese had a visionary idea for Metro's architecture. His clean and monumental design aimed to be the antithesis of New York's subway, with its graffiti, low ceilings and industrial appearance. Zachary M. Schrag describes the concept in his definitive book The Great Society Subway:

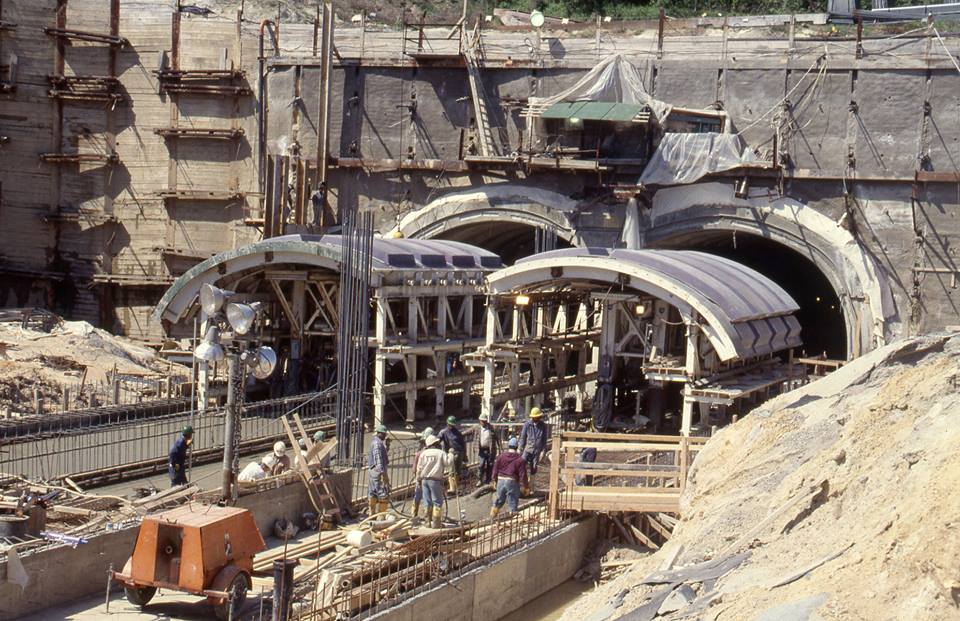

"Weese proposed vaults, turning stations into underground equivalents of classic nineteenth-century rail stations, with their cast-iron trainsheds ... Vaults allowed him to dispense with columns, improving sightlines and giving trainrooms a sense of spaciousness."

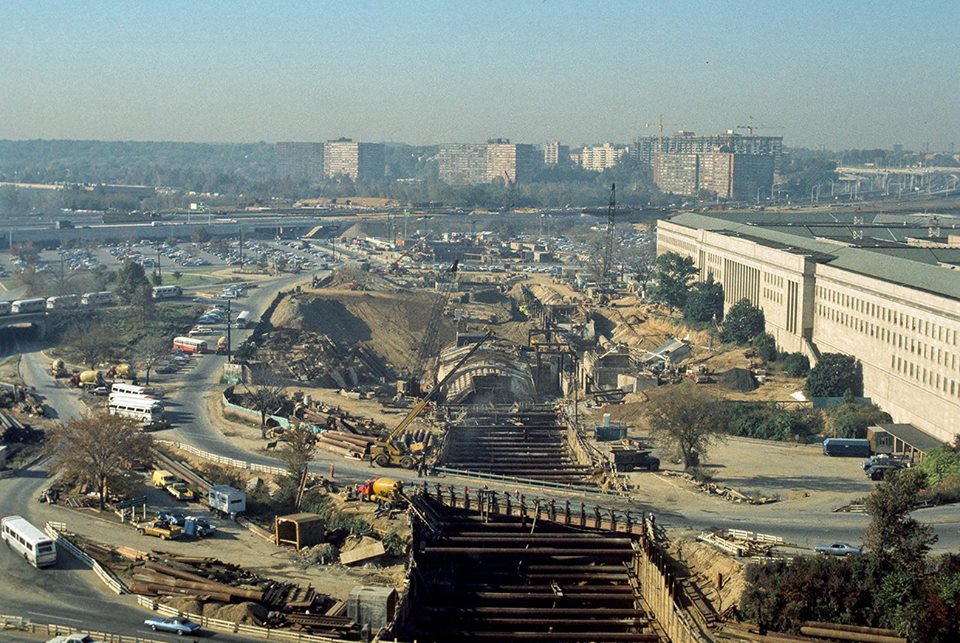

Most of the stations were excavated using a technique called cut and cover. Builders would reroute utilities, dig a trench, roof it over and rebuild on the surface. They wanted to minimize the number of buildings that had to be torn down, so most of the cuts were under public property. Tunnels follow major streets and the stations were placed in parks and plazas where possible. Deeper stations like Dupont Circle, Woodley Park, Cleveland Park and Van Ness had to be blasted through rock.

Some demolition was unavoidable where the tunnels curved. Trains can't turn on a dime, so a number of corner buildings were torn down to create gentle bends.

Digging around historic buildings posed unique challenges. The Washington Star wrote in in 1975 that:

"Metro has been plagued by cracks in walls and building owners' complaints. The Lincoln Room of the National Portrait Gallery suffered severe cracks during construction about four years ago and special shoring was necessary. Two years ago there was a cave-in at Connecticut and M Streets NW in which nearby buildings were evacuated, although no structural damage occurred. The worst damage occurred in the 100 block of D Street SW, where two buildings more than 100 years old nearly collapsed and Metro had to use steel cables to hold them together."

Metro construction at the national portrait gallery. wmata photo

There were also some only-in-DC problems. The Great Society Subway notes that "near the White House, engineers were warned away from secret communications links, including the famous Hot Line to Moscow."

Construction on Metro continues to the present day, and the system now boasts 91 stations.

Looking beyond the safety and maintenance problems of the last two years, it is important to appreciate what a marvel Metro is, and how it has shaped Washington.

It keeps hundreds of thousands of drivers off the roads, and its stations have become magnets for transit oriented development.

Additional construction photos are below. If you enjoyed this article you might also like the 1908 and 1967 proposals for a DC subway system.