Tents on the American University campus. Library of Congress photo

The Spring Valley neighborhood next to American University is built on top of a World War I-era chemical weapons experiment station. From 1917 to 1920, researchers here cooked up deadly gas weapons and tested them in the nearby fields.

When the US entered World War I in 1917 American University was a struggling institution with 28 students, located in the undeveloped hills above of Washington.

The university's president wrote a letter to "his excellency Woodrow Wilson" offering the school "for such purpose as the Government may desire. The campus may be used either for a camping ground for troops, for gardening and raising products for the Army, or for such other purpose as you may elect."

Secretary of the War Newton Baker took him up on the offer and established The American University Experiment Station, the nation’s largest chemical weapon facility. A thousand chemists were assembled to develop cutting edge Mustard Gas and Lewisite weapons for the nascent Gas Service Section.

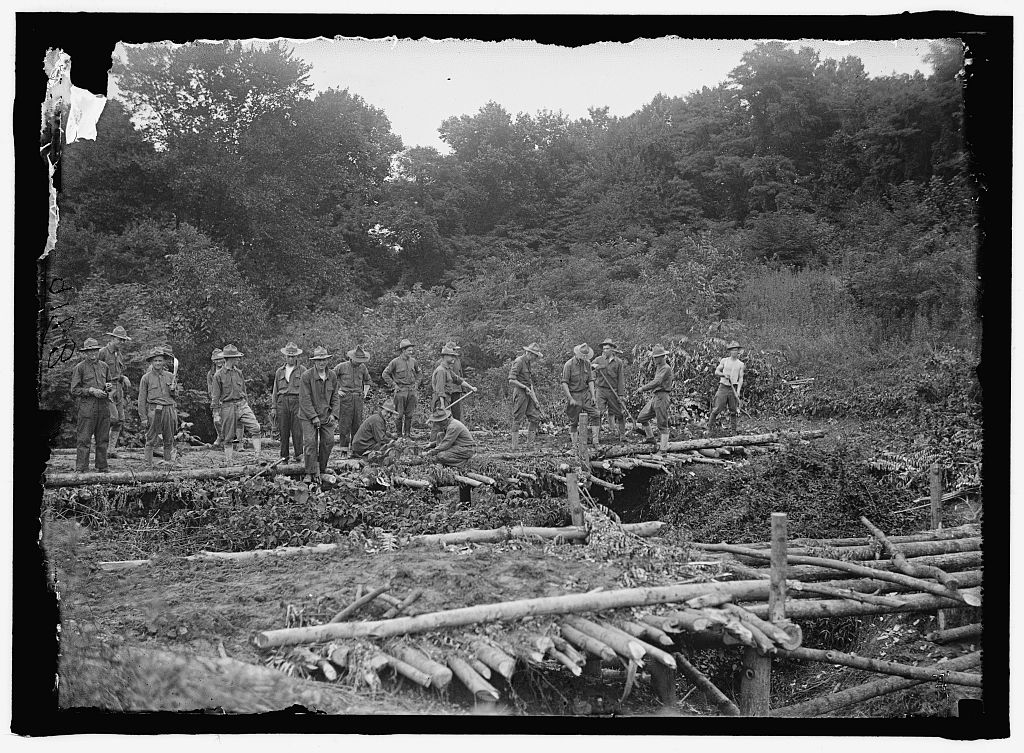

They tested their concoctions on-site over mock trenches and dugouts meant to simulate conditions on the Western Front. It must have been a bizarre spectacle for Washington residents; imagine seeing mortar crews on the AU campus launch gas shells at goats and stray dogs tethered over by Little Falls Park.

One of these firing ranges acquired the moniker “Mustard Field” as a result of its frequent bombardments - it’s located at the current intersection of 49th Street and Sedgewick Street NW.

These poison gas experiments didn’t pose the public health threat you may be imagining - these were individual gas shells in an unpopulated area. The small clouds of gas would have quickly dissipated into the breeze. (On the battlefield, gas attacks were often on the scale of tens of thousands of shells.)

By 1919 the war was over and the Army began the process of closing down the American University Experiment Station. The trenches were filled in and tents were packed up. According to the American University Eagle, the DC Fire Department burned down 70 temporary buildings on campus that were "so impregnated with toxic ingredients that they were unsuitable for student use.”

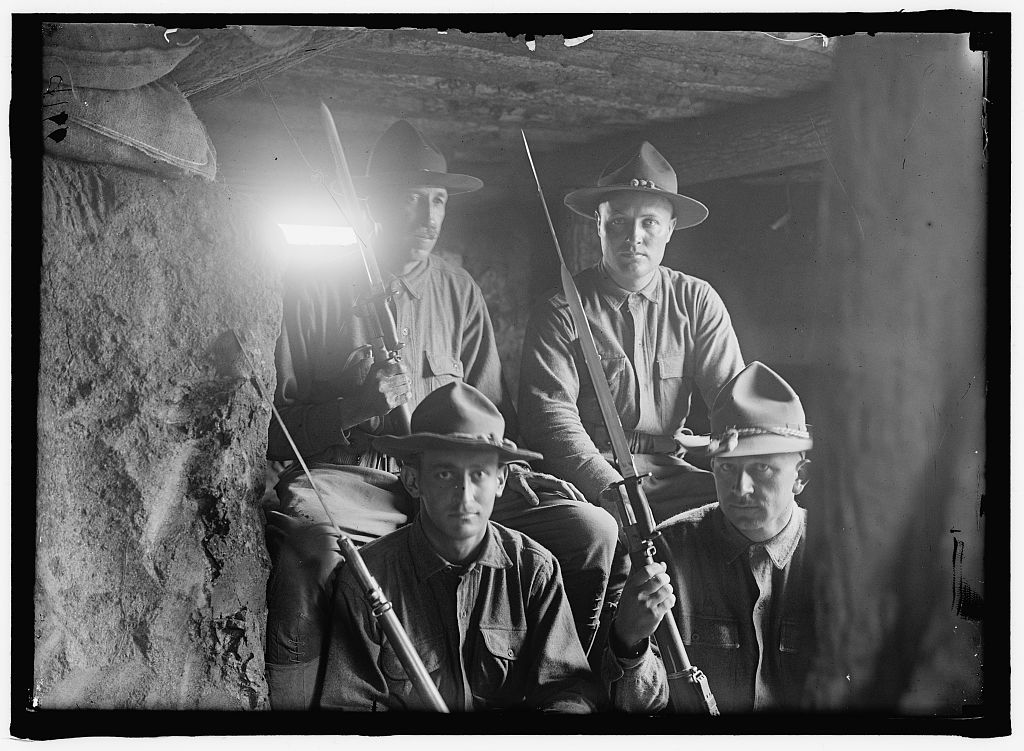

"The hole called hades". Library of Congress photo

The massive stockpile of chemical shells and poison was more complicated to dispose of. The Army buried most of it in pits on the southern edge of campus. The photo above shows Sergeant Charles Maurer at the largest disposal sites. The back of the photo bears the following caption:

“The most feared and respected place on the grounds. The bottles are full of mustard, to be destroyed here. In Death Valley. The hole called Hades.”

Within a decade houses began to pop up in the area as Spring Valley emerged as a upscale early suburb, and the public simply forgot about the deadly chemicals under their feet.

4825 Glenbrook road. Google Earth image

The buried chemical munitions were rediscovered in 1993 by a construction crew working on a utility trench. Over the next year the Army Corps of Engineers unearthed and removed almost 200 old World War 1 era shells. Additional discoveries were made in 2000 and 2007. In 2013 they found the “hole called Hades” depicted in the photograph above. It was underneath a house at 4825 Glenbrook Road.

If you scroll over to the address on Google Earth you can see that the house has been torn down and the property is encased in a massive aluminum barn structure. Inside, hazmat protected specialists have been working to meticulously excavate the deadly pit. Four sirens on the corners of the barn are rigged to sound if any poison gas escapes. Residents have been trained to shelter in place if they hear the alarms go off.

When the diggers unearth munitions or chemical glassware, it is transported by helicopter to a federal property next to Dalecarlia Reservoir, where it is safely destroyed. The Army Corps of Engineers hope to wrap up the project by 2017.

Here are some additional photos of of the American University Experiment Station during World War 1 via the Library of Congress: