view of sand silos and manholes. Roof Access or Bust Photo

This is part three in a series of articles about DC’s water supply. Be sure to also check out the Washington Aqueduct and the Lydecker Tunnel Fiasco.

Typhoid epidemics regularly swept across Washington at the turn of the century as the population increased and industrial pollution worsened. A chief culprit was the city water supply. The unfiltered Washington Aqueduct carried a stream laced with bacteria and a notorious amount of Potomac mud, described by a contemporary Washington Post reporter as a “Seal-brown mixture of water and real estate.”

Shortly after the new city reservoir was completed at Howard University, Congress authorized funds for an adjacent filtration site to address the public health situation.

The facility relied entirely on sand to clean the water; at the time this method scaled better and was more cost effective than using chemicals.

“Raw water” came in from the reservoir next door and slowly percolated through the sand in 25 vaulted underground cells before making its way out into District taps. The four foot lining of sand actually did a remarkable job at removing bacteria and sediment from the water.

Inside the filtration cells. Roof Access or Bust photo

According to a historic preservation report, the sand was brought in from Laurel, Maryland on the B&O Railroad and “went through an extensive preparation process to meet specifications for cleanliness, removing all traces of clay and other undesirable particles.”

According to a 1924 Washington Post description, “about every six months a thin layer is removed, washed in a machine and restored . . . every two or three years the entire filter surface resanded.”

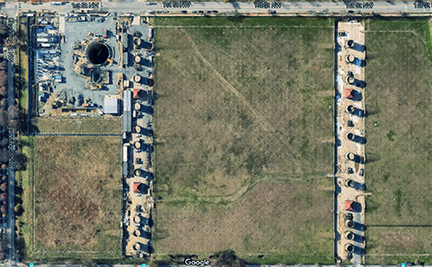

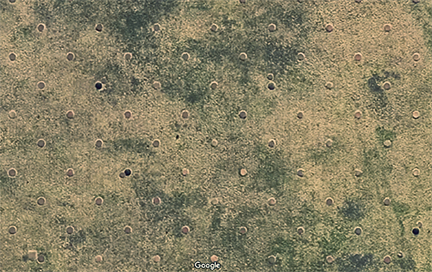

Enormous quantities of fresh sand were stored above ground in parallel rows of stubby concrete silos. Engineers could shovel it out when necessary and drop it down into the cells through 2,100 manholes that are visible in satellite imagery.

Improvements like the Washington Aqueduct and the McMillan Sand Filtration Site came to DC as part of the City Beautiful reform movement. It’s backers aimed to benefit society by taking on the squalid urban conditions of the Industrial Revolution.

At the time there was a different, more positive image of Washington’s water supply as a Public Work, and not merely a piece of infrastructure. As such, the nation’s foremost landscape architect was called into devise a plan to pretty up the filtration site.

Sand Silos. Robin Buck photo

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. designed a public park at the McMillan Sand Filtration Site that became an important community gathering place for northeast District residents.

Olmsted’s plantings and perimeter pathway were designed to complement the “interesting and remarkable” appearance of the sand storage towers, the walls of which he covered in ivy.

For a time it was a popular destination for picnics, outdoors activities, or a quiet stroll away from the bustle of city life. Unfortunately, the park was fenced off for security reasons during World War II and never reopened.

DC city government purchased the McMillan Sand Filtration Site after it closed in 1986 but the land has been abandoned and largely untended. It is a fantastic opportunity for preservation and a redevelopment project similar to New York’s High Line. Hopefully, visitors will one day be able to explore it its unique spaces, and the site won’t become another block of boring apartments.

Check out these images of the early days at the McMillan Sand Filtration Site, via the Washington Aqueduct archives: